This is the continuation of Overeating and Obesity 2021 Update on What We Know and What Medicine-Surgery Can Do.

Medications or Surgery for Obesity – Pharmacological Treatment of Food Addiction, Overeating, and Obesity

As Kelly Brownell and I described in our Oxford University Press book on Food Addiction [20], this behavioral addiction has a great deal in common with substance use disorders [21]. It is all-too-common for people to eat a diet that they know is not very healthy. We also might start under control but then eat more than we intend. We eat foods that we know we shouldn’t.

Physician or family admonitions only go so far, and even warnings about consequences such as high blood pressure, cancer risks, type 2 diabetes, and joint/bone pain can’t stop us from unhealthy eating. Loss of control over highly enjoyable foods, like pizza or ice cream, leads to eating more than intended, eating pain and discomfort. Just eating to the point of physical, psychological, and social distress can characterize many food addicts. Failed diets and abortive attempts to control overeating, preoccupation with food and eating, shame, anger, and guilt look like traditional addictions.

We live in a time when food is in abundance, manufactured, and available on demand. Highly palatable and so-called “fast food” can produce similar effects as drugs of abuse [22]. Highly processed foods, many with added fats and/or refined carbohydrates, can trigger an addictive-like process.

Recently, people who consume large amounts of these foods have been studied by researchers. Surprisingly, when they try to stop or cut down on these foods, they have emotional distress, including withdrawal symptoms. Processed food withdrawal syndrome is characterized by affective, cognitive, and physical symptoms that may bias food choices.

A recently developed scale by Gearhardt’s group of highly processed food withdrawal in adults (ProWS) provides this novel clinical evidence of highly processed food withdrawal. Obesity is a subtype of Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS), and these new strategies in the treatment and prevention of obesity target improved dopamine function [23]. These findings reinforce the idea that overeating and obesity may be candidates for consideration as Addictive Diseases.

One likely outcome of such thinking would be that we might find that new pharmacological treatments could be developed rather than suppressing appetite, actually interfering with sugar or fat or hedonic foods from accessing and changing the brain’s reinforcement areas. More extreme analgesic effects of sucrose in the neonate were associated with the most massive future increases in WLZ- higher birth weight, length, or WLZ scores.

Greater opioid-mediated newborn behavioral response to intraoral sucrose may be a marker for future obesity risk [24]. As we have found in alcohol use disorders, naltrexone can reduce drinking alcohol and alcohol-related problems by blocking, in this case, alcohol-related endorphin release and reward. These behavioral food addictions might be considered viable and testable addiction disease-like entities, producing novel approaches and treatments for a significant disease of unknown cause and without obvious, fast, and effective treatment.

Some evidence exists supporting the idea that treating overeating might be successfully achieved by using anti-addiction medications. The best examples are Phentermine-Topiramate (tradename Qsymia®) and Naltrexone-Buproprion (tradename Contrave®). Before this combination, we did use Bupropion to reduce appetite.

Nowadays, Bupropion also increases energy expenditure through increased dopamine activity and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) activation. These agents do cause weight loss, but it is modest in many clinical studies. These medications are approved for obesity and are also medications used in alcohol use disorders, nicotine use disorders, and opioid use disorders.

Other obesity medications included the selective serotonin receptor agonist Lorcaserin (tradename Belviq®), which has also been tried in marijuana use disorders before the manufacturer recalled this medication. But again, many of the current weight management clinics and medical treatment of obesity programs had used GLD-1 agonists off label until the recent approval of Saxenda® (liraglutide).

Other obesity medications included the selective serotonin receptor agonist Lorcaserin (tradename Belviq®), which has also been tried in marijuana use disorders before the manufacturer recalled this medication. But again, many of the current weight management clinics and medical treatment of obesity programs had used GLD-1 agonists off label until the recent approval of Saxenda® (liraglutide).

Saxenda is an FDA-approved, prescription injectable medicine that may help some adults with excess weight. Usually, the prescriber tries to add this to a diet and exercise regimen for patients with obesity and who also have weight-related medical problems (such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or type 2 diabetes).

Saxenda (liraglutide) is similar to a naturally- occurring hormone that helps control blood sugar, insulin levels, and digestion. Saxenda is approved and prescribed in adult patients with an initial body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater (obesity) or 27 kg/m2 or greater (overweight) in the presence of at least one weight-related comorbid condition (e.g., hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia).

While safe and effective, it is primarily viewed as an adjunct in obese patients willing to start a reduced-calorie diet and increase exercise for chronic weight management. Patients treated with Saxenda should be monitored for depression, worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or behavior.

Avoid Saxenda in patients with a history of suicidal attempts or active suicidal ideation. Saxenda is not a weight-loss medicine or appetite suppressant. Semaglutide and exenatide are GLP-1 receptor agonists with marketing authorization to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Intragastric Balloons

Medical, surgical, and endoscopic weight loss is undergoing an explosion of new techniques and devices. Many more exciting advances have been in bariatric surgeries, but endoscopic approaches rather than the conventional and more invasive laparoscopic or open surgical approaches are gaining traction. Many balloons ReShape the FDA approved duo IGB in 2015 for patients with a BMI between 30 and 40kg/m2 with one obesity-related comorbidity.

Balloons work and are safe [25] and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for weight loss: the Orbera™ Intragastric Balloon System (Apollo Endosurgery Inc, Austin, TX, United States), the ReShape® Integrated Dual Balloon System (ReShape Medical, Inc., San Clemente, CA, United States), and the Obalon (Obalon® Therapeutics, Inc.). The individual features of each of these balloons, the method of introduction and removal, and the expected weight loss and possible complications are discussed in a recent review of the various balloons in weight loss [26].

Intragastric balloons (IGB) facilitate weight loss by reducing the stomach’s potential volume, inducing early satiety, and altering gastric motility. Reductions in gastric hormone secretion such as cholecystokinin and pancreatic polypeptide may reflect delayed gastric emptying and improve glucose metabolism.

Furthermore, changes in appetite-regulating hormones such as ghrelin were significantly decreased in patients with IGB, leading to reduced hunger and more significant weight reduction. Weight loss is rapid with the IGBs. Most of the weight that is lost is lost during the first four months after the balloon is placed [27].

While IGBs cause weight loss, some patients lose more than others. Expected losses of 15 percent of body weight is typical. In a randomized clinical trial with 255 adults with a BMI of 30 – 40, people who had the IGB and behavioral therapy lost 29 percent of their excess weight, compared to only 14 percent in a group that only received behavioral therapy [28].

While IGBs cause weight loss, some patients lose more than others. Expected losses of 15 percent of body weight is typical. In a randomized clinical trial with 255 adults with a BMI of 30 – 40, people who had the IGB and behavioral therapy lost 29 percent of their excess weight, compared to only 14 percent in a group that only received behavioral therapy [28].

Intragastric balloons have been used since 1985 to bridge the obesity treatment gap between those patients with obesity and those who do not qualify for bariatric surgery because they do not have a high enough BMI. Intragastric balloons have been used with the benefits of being minimally invasive but still required endoscopy.

The Elipse intragastric balloon (EIGB) [29] is a swallowable balloon spontaneously excreted through a natural orifice at approximately 16 weeks. Severe adverse events are rare, and the rate of early removal is low.

Several concerns exist, including the treatment efficacy and risk of bowel obstruction. This 2020 meta-analysis demonstrates that EIGB is a safe device offering a significant weight loss that warrants further studies for its long-term weight loss outcomes.

Bariatric Surgeries for Obesity

Obesity is associated with increased mortality directly due to common co-occurring obesity-associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory dysfunction, some carcinomas, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and orthopedic degenerative diseases. Medications may be developed approved by the FDA as safe but do not produce enough weight loss and disease reversal to rival bariatric surgeries’ efficacy.

Modern bariatric procedures have strong evidence of effectiveness and safety. Recent long-term studies suggest that bariatric surgeries are under-utilized. Experts recommend that all patients with severe obesity-and, especially those with type 2 diabetes, be engaged by their health providers in a shared decision-making conversation about bariatric surgery risks and benefits. Patients can always continue usual medications, diet, and lifestyle treatments, but they should be presented with the most current data to inform their decisions.

Bariatric surgeries [30] are the most effective anti-obesity treatments. The 1991 National Institutes of Health guidelines recommended considering bariatric surgery in patients with a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 40 or higher or 35 or higher with obesity-related severe comorbidities. These guidelines are still widely used.

But, some experts suggest that in 2020 bariatric surgeries are now safer and should be seriously considered for all patients with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of 30 to 35. These surgeons point to the compelling evidence indicates that surgery results in more significant improvements in weight loss and type 2 diabetes outcomes than nonsurgical interventions, regardless of the type of procedures used.

Bariatric surgery can reverse hypertension, diabetes, and other obesity-related diseases, which imperil the patient’s life. The two most common techniques used currently, the sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass, have similar effects on weight loss and diabetes outcomes and similar safety through at least a 5-year follow-up. However, in a recent study summarizing the data, it does seem that the sleeve procedure is associated with fewer reoperations, and the bypass procedure may lead to longer-lasting weight loss and glycemic control [31].

Bariatric Surgery complications and risks include operation and anesthesia-related risks and the chances of switching from food to alcohol or drugs. Undergoing either of the most common bariatric surgeries for weight loss (RYGB versus LAGB) is associated with twice the risk of alcohol use disorder symptoms [32].

One-fifth of participants reported incident AUD symptoms within five years post-RYGB. Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD ) education, screening, evaluation, and treatment referral should be incorporated in pre- and postoperative care. Longer follow-up of patients for changes in alcohol and drug use is needed for those patients who have had bariatric surgeries for weight loss is necessary [33].

Bariatric appears to be an incredibly effective treatment for morbidly obese patients who also meet food addiction (FA) diagnostic criteria using the Yale Food Addiction test. According to a study by Sam Klein’s group, Surgery-induced weight loss resulted in remission of FA in 93% of FA subjects; no new cases of FA developed after surgery.

Surgery-induced weight loss decreased food cravings and emotional and external eating behaviors in both groups. Bariatric surgery-induced weight loss induces remission of FA and improves several eating behaviors that are associated with FA [34].

Anti-Obesity Medications Plus Surgery

Recently, experts have studied the possible role of anti-obesity medications in slowing or reducing the chance of weight regain (WR) after bariatric surgery. In one study, The medication Phentermine and Topiramate combination is safe and effective in mitigating post-bariatric surgery WR.

Recently, experts have studied the possible role of anti-obesity medications in slowing or reducing the chance of weight regain (WR) after bariatric surgery. In one study, The medication Phentermine and Topiramate combination is safe and effective in mitigating post-bariatric surgery WR.

In 2016, Schwartz et al. [35] retrospectively reviewed 65 patients who experienced postoperative WR or weight plateau and treated them with anti-obesity medication Phentermine or the anti-obesity combination Phentermine-Topiramate. Like Istfan et al. [36], they concluded that medications can slow or reverse WR. In another larger multicenter trial, 319 patients were treated for WR after bariatric/metabolic surgery [37] showed similar results and, additionally, evidence of Topiramate enhancement of weight loss.

These data suggest that the future may not be either bariatric surgery or diet-lifestyle-exercise or medications but instead all three with group and other therapies. Randomized and prospective trials will help us understand the ideal approach to weight loss and diabetes reversal in 2021.

Please See – Overeating and Obesity 2021 Update on What We Know and What Medicine-Surgery Can Do – Part 1

Resources:

20. https://www.amazon.com/Food-Addiction-Comprehensive-Kelly-Brownell/dp/0199374570

21. https://blog.oup.com/2012/08/food-addiction/

22. https://blog.oup.com/2012/08/food-addiction/

23. Blum K, Thanos PK, Wang GJ, Febo M, Demetrovics Z, Modestino EJ, Braverman ER, Baron D, Badgaiyan RD, Gold MS. The Food and Drug Addiction Epidemic: Targeting Dopamine Homeostasis. Curr Pharm Des. 2018 Feb 12;23(39):6050-6061. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170823101713. PMID: 28831923.

24. Lumeng JC, Li X, He Y, Gearhardt A, Sturza J, Kaciroti NA, Li M, Asta K, Lozoff B. Greater analgesic effects of sucrose in the neonate predict greater weight gain to age 18 months. Appetite. 2020 Mar 1;146:104508. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104508. Epub 2019 Nov 4. PMID: 31698014; PMCID: PMC6954956.

25. Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Alvarez EE, Sendra-Gutiérrez JM, González-Enríquez J. Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2008 Jul;18(7):841-6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9331-8. Epub 2008 May 6. PMID: 18459025.

26. Vyas D, Deshpande K, Pandya Y. Advances in endoscopic balloon therapy for weight loss and its limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Nov 28;23(44):7813-7817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i44.7813. PMID: 29209122; PMCID: PMC5703910.

27. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/endoscopic-weight-loss-program/services/balloon.html

28. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/endoscopic-weight-loss-program/services/balloon.html

29. Vantanasiri K, Matar R, Beran A, Jaruvongvanich V. The Efficacy and Safety of a Procedureless Gastric Balloon for Weight Loss: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg. 2020 Sep;30(9):3341-3346. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04522-3. PMID: 32266698.

30. Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and Risks of Bariatric Surgery in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2020 Sep 1;324(9):879-887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12567. PMID: 32870301.

31. Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and Risks of Bariatric Surgery in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2020 Sep 1;324(9):879-887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12567. PMID: 32870301.

32. King WC, Chen JY, Courcoulas AP, Dakin GF, Engel SG, Flum DR, Hinojosa MW, Kalarchian MA, Mattar SG, Mitchell JE, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Steffen KJ, White GE, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ. Alcohol and other substance use after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a U.S. multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Aug;13(8):1392-1402. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.021. Epub 2017 Mar 31. PMID: 28528115; PMCID: PMC5568472.

Cop

33. Briegleb M, Hanak C. Gastric Bypass and Alcohol Use: A Literature Review. Psychiatr Danub. 2020 Sep;32(Suppl 1):176-179. PMID: 32890386.

33. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) is the largest national society for this specialty. The vision of the Society is to improve public health and well-being by lessening the burden of the disease of obesity and related diseases throughout the world. ASMBS describes and illustrates (https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures) the common bariatric procedures:

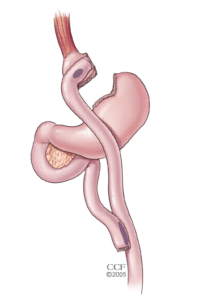

33. Gastric Bypass – The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass – often called gastric bypass – is considered the ‘gold standard’ of weight loss surgery.

33. Gastric Bypass – The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass – often called gastric bypass – is considered the ‘gold standard’ of weight loss surgery.

Advantages

- Produces significant long-term weight loss (60 to 80 percent excess weight loss)

- Restricts the amount of food that can be consumed

- May lead to conditions that increase energy expenditure

- Produces favorable changes in gut hormones that reduce appetite and enhance satiety

- Typical maintenance of >50% excess weight loss

Disadvantages

- Is technically a more complex operation than the AGB or LSG and potentially could result in greater complication rates

- Can lead to long-term vitamin/mineral deficiencies particularly deficits in vitamin B12, iron, calcium, and folate

- Generally has a longer hospital stay than the AGB

- Requires adherence to dietary recommendations, life-long vitamin/mineral supplementation, and follow-up compliance

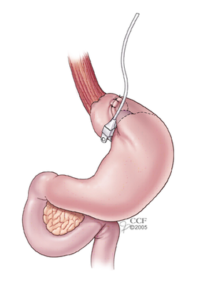

33. Adjustable Gastric Banding

33. Adjustable Gastric Banding

The Adjustable Gastric Band – often called the band – involves an inflatable band that is placed around the upper portion of the stomach, creating a small stomach pouch above the band, and the rest of the stomach below the band.

Advantages

- Reduces the amount of food the stomach can hold

- Induces excess weight loss of approximately 40 – 50 percent

- Involves no cutting of the stomach or rerouting of the intestines

- Requires a shorter hospital stay, usually less than 24 hours, with some centers discharging the patient the same day as surgery

- Is reversible and adjustable

- Has the lowest rate of early postoperative complications and mortality among the approved bariatric procedures

- Has the lowest risk for vitamin/mineral deficiencies

Disadvantages

- Slower and less early weight loss than other surgical procedures

- Greater percentage of patients failing to lose at least 50 percent of excess body weight compared to the other surgeries commonly performed

- Requires a foreign device to remain in the body

- Can result in possible band slippage or band erosion into the stomach in a small percentage of patients

- Can have mechanical problems with the band, tube or port in a small percentage of patients

- Can result in dilation of the esophagus if the patient overeats

- Requires strict adherence to the postoperative diet and to postoperative follow-up visits

- Highest rate of re-operation

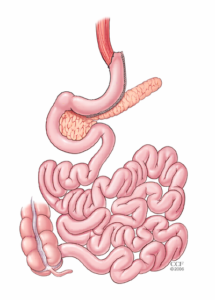

33. Sleeve Gastrectomy

33. Sleeve Gastrectomy

The Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy – often called the sleeve – is performed by removing approximately 80 percent of the stomach. The remaining stomach is a tubular pouch that resembles a banana.

34. Pepino MY, Stein RI, Eagon JC, Klein S. Bariatric surgery-induced weight loss causes remission of food addiction in extreme obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014 Aug;22(8):1792-8. doi: 10.1002/oby.20797. Epub 2014 May 23. PMID: 24852693; PMCID: PMC4115048.

35. Schwartz J, Chaudhry UI, Suzo A, et al. Pharmacotherapy in conjunction with a diet and exercise program for the treatment of weight recidivism or weight loss plateau post-bar- iatric surgery: a retrospective review. Obes Surg 2016;26:452-458.

36. Istfan NW, Anderson WA, Hess DT, Yu L, Carmine B, Apovian CM. The mitigating effect of phentermine and topiramate on weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1023-1030.

37. Stanford FC, Alfaris N, Gomez G, et al. The utility of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery for weight regain or inadequate weight loss: a multicenter study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:491-500.

About the Author:

Mark S. Gold, M.D., Professor, Washington University School of Medicine – Department of Psychiatry, served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014. He was the first Faculty from the College of Medicine to be selected as a University-wide Distinguished Alumni Professor and served as the 17th University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Professor.

Mark S. Gold, M.D., Professor, Washington University School of Medicine – Department of Psychiatry, served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014. He was the first Faculty from the College of Medicine to be selected as a University-wide Distinguished Alumni Professor and served as the 17th University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Professor.

Dr. Gold is also a Distinguished Fellow, American Society of Addiction Medicine; Distinguished Life Fellow, the American Psychiatric Association; Distinguished Fellow, American College of Clinical Pharmacology; Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Tulane University School of Medicine; Professor( Adjunct), Washington University in St Louis, School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; National Council, Washington University in St Louis, Institute for Public Health

Learn more about Mark S. Gold, MD

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of addictions. These are not necessarily the views of Weight Hope, but an effort to offer a discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Weight Hope understand that weight issues result from multiple physical, emotional, environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from a weight concern, please know that there is hope for you.

Published on November 9, 2020. Published on WeightHope.com

Reviewed by Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on November 9, 2020